HAYAT TAHRIR AL-SHAM AND IMAGINED COMMUNITIES IN ITS PROTO-STATE March 1, 2023

In recent years, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) has been attempting to develop its own polity. This process has not been linear and there has been a maturation process over time. Beyond governance though, an important part of nation-building is creating a similar narrative of people’s own history and shared memory. As Benedict Anderson notes in his famous Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, nations or “imagined communities” are socially constructed, since not everyone in a polity knows someone, but are believed to share a similar history and experience. This is no different for HTS, which has since mid-August been publishing “briefs” through its municipal governance structure the “Administration for the Liberated Areas” on different cities, villages, and regions in the areas it controls. Therefore, there is an interplay that HTS is attempting to build between different areas it controls, connecting real world history that will hopefully bring people in its territory together to illustrate their similarities and thus establishing an “imagined community” amongst HTS’s polity.

Another component of this campaign, which is different from how Anderson theorized the “imagined community” previously, is that similar to the printing press playing a role in bringing many Western nations together through similar ideas and narratives, so too does this take place now, but via social media, used by these newer proto-states in the 21st century. For one, these briefs are originally published online via official Telegram accounts for the different municipal administrations (Ariha, Atme, Central Region, Harim, Idlib, Jisr al-Shughur, Northern Region, and Sarmada) in HTS territory. What’s more, these briefs are published in blocked graphic formats similar to how activists in the West create easily digestible infographics to share on platforms like Instagram that can be posted to one’s stories — and thus creating greater virality. This potential to repost this content to more mainstream platforms beyond Telegram highlights HTS’s parallel real-world struggle to garner local and/or International legitimacy for its political and state-building project and to no longer be seen as an extreme anathema, but within a more accepted discourse. Therefore, it is not surprising that HTS has moved beyond attempts to get off the U.S. terrorism list towards attempting to return its online apparatus to more mainstream platforms like Twitter and no longer just to the deep corners of the Internet, like its former comrades and now enemies in the Islamic State and al-Qaeda.

Details on the Briefs

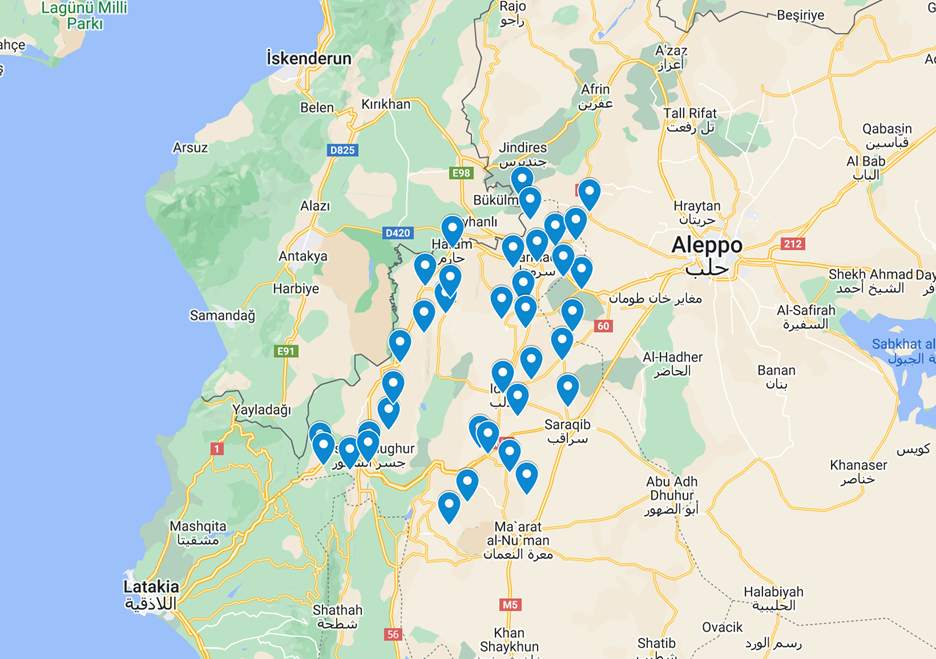

As of February 28, 2023 there have been 39 briefs published on the following locations: Idlib, Harim, Ariha, al-Atarib, Sarmada, Salqin, Binnish, Jisr al-Shughur, Atme, Taftanaz, Kafr Najd, al-Dana, Darat ‘Iza, Wadi Murtahun, Armanaz, Bidama, Qminas, al-Marj al-Akhdar, Muntaf, Halluz, Afes, Aqrabat, Kafr Takharim, Kafr Karmin, Kafr Dariyan, al-Najiya, Killi, Haranabush, Jabal al-Zawiyah, Ketyan, D1weila, Ihsim, Kafr Yahmul, Termanin, the al-‘Asi (Orontes) river, water features in the Jisr al-Shughur region, the Pomegranate festival in Darkush, the hamams of Shaykh ‘Isa, and the history of earthquakes in the region following 7.8-magnitude quake on February 6, 2023. Illustrating the wide breadth of this campaign to build an “imagined community” that goes beyond just the biggest and most known locales in HTS-controlled territory.

At first, the briefs detail the location of the area, which cities or villages it is located near, its proximity to Idlib, and sometimes even the area’s location above sea level. This way, it showcases how connected all these cities, villages, and locales are to one another as one political unit and thus building the “imagined community” together. Furthermore, the briefs highlight both the agricultural prowess of the areas and the main sources of water for the area, indicating an attempt by the group to demonstrate its success in securing these resources for its people. For example, according to the brief on the town of Harim, it is known for its trees and gardens as well as where apricots, walnuts, olives, and figs are grown. Likewise, Harim has “abundant water supplies, due to abundant rainfall and the presence of seven freshwater springs,” which according to the brief, historians thus called it “little Damascus” due to the presence of so many streams.

The “briefs” also describe important historical landmarks in each area, including ancient carved stone structures, as well as the origins of the town’s name, often in Aramaic or Syriac. It is clear that HTS seeks to highlight the rich history and culture that makes the area unique in the hopes of inspiring a sense of national pride within its territory. For instance, Ariha is described as an ancient city and allegedly has some archeological sites dating back 5,000 years. Likewise, the town of al-Atarib is located next to an ancient roman fortress, Deir Amman. Similarly, Darat ‘Iza “contains residential caves from thousands of years ago as well as Aramaic ruins, and remains of Roman and Byzantine monasteries and dwellings.” As for the names, for example, in Syriac, the town of Armanaz means “land of the king Naz,” while in Aramaic, Bidama means “home of the nation.”

Finally, the posts typically end by detailing the role of the city or village in the Syrian revolution, honoring the area’s commitment to resisting the Assad regime and the sacrifices the area made to support this cause. These sections may indicate the group’s efforts to signal its gratitude and care for its people and the suffering they face in service of the revolution, representing another soft-power attempt to increase popular support for the organization that attempts to serve as the symbol of the revolution itself. For instance discussing al-Najiya village, its brief notes that the “town has been subject to mass displacement due to repeated airstrikes by the Assad regime, including cluster and barrel bombings, as punishment for rebellion.” Moreover, Killi village “participated in the revolution from its beginnings, and the people stood in demonstrations asking for justice and the fall of the Assad regime. Now, Killi hosts dozens of IDP camps.”

Takeaway

These city and village briefs, posted on the group’s social media channels, represents yet another soft power effort by HTS to enhance popular support and build a more robust “imagined community” as part of its state-building project. Although the success of these briefs in increasing public support for HTS is difficult to measure, its publication adds an interesting dimension to the ways in which insurgents transitioning to state-power can utilize social media to connect their various territories and ways for locals to then take pride in the broader history and culture in their cities and villages and repost it themselves on platforms like Instagram. Thus, linking HTS’s real world efforts for legitimacy with its online campaigns to foster community and further consolidating its hold as rulers of this nascent polity.