TELEGRAM DEPLATFORMING ISIS HAS GIVEN THEM SOMETHING TO FIGHT FOR

Telegram became the epicenter of terrorist propaganda. Speeches by leadership, martyrdom notices, attack claims, and weekly news releases were shared there. Researchers who, just a decade or two ago, had to wait for terrorist groups to release their grainy videos from mountain hideouts to get a sense of what these groups wanted to communicate to the world now had on their smartphones access to tens of thousands of posts unrelentingly pushed out daily.

What some researchers missed early on while paying attention to the deluge of content being sent their way, was the personal friendships and bonds being formed among ISIS supporters. There was an assumption that because these ISIS supporters would never meet in real life, that their “friendship” wasn’t real. Around this time in 2013, I started interviewing ISIS fighters and ISIS supporters on another platform they used back in the day: KIK Messenger. What became clear, especially when talking to the ISIS support network around the world, was that they loved each other, knew each other on a deep and personal level, and took immense risks for each other. They checked in on each other when they were sick, they encouraged each other when it was exam season at their universities, and some even got married over Skype to people they would probably never meet in real life. They called themselves the baqiya (Arabic for “remaining”) family.

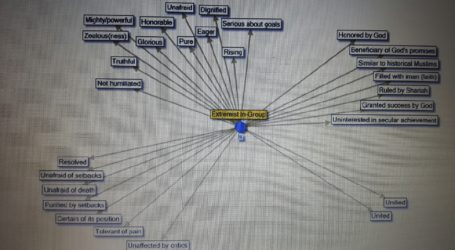

We tend to think of the internet as a place where young people go to experiment with new and fantastical identities. They are who they are in real life, we assume, and the online space is a space for experimentation. For some young Muslims—and now, I would say this is very much true for young neo-Nazis as well—the internet is the exact opposite. It is in their “real life” communities where they feel like they are pretending and where they feel like they aren’t being their true selves. In the online space, connected to a global brotherhood and sisterhood of like-minded people, each undergoing similar identity struggles, they find a home, find a community, and find themselves. This bond isn’t fake or superficial—it is realer than anything they have experienced before. They feel understood.

When social media companies like Twitter, then, started targeting these online jihadist communities, it had two discernible impacts on ISIS supporters. Some simply vanished and moved on with their lives. When I texted one supporter during this period, he replied that he had gotten married and was expecting a child. I never heard from him again. Another replied that she “got busy with school.” In other words, the disruption by social media companies itself gave some young people the space to think and do something different. Six years on from ISIS’s heyday on mainstream social media, these individuals are six years older and many have largely moved on to other things.

Others, importantly, doubled down and became hyper-committed to the cause. For them, the very act of getting suspended, collectively strategizing ways to get back online, helping fellow supporters prop up their accounts and networks all became personally, emotionally, and socially significant. It was life in the online foxhole, and they were being attacked from all sides. Playing a role in ISIS’s cyber frontline was hugely rewarding for many—and now these lines are once again shifting, and they need reinforcements. The fight will also attract a new generation of recruits.

It is this point that the text from my friend—who even as a researcher feels like he is taking part in something new and exciting—brings home. ISIS’s zenith in the online space saw dozens of young people whose bonds were forged and solidified in the weeds of that struggle, in that act of fighting, to stay alive online. The intensity of that fight largely died down as the network moved to Telegram and was allowed to remain functional. Now they are fighting again.

The ongoing policy debates around deplatforming groups like ISIS continues unabated. On the one hand, a platform like Telegram may have been the perfect home for the Islamic State. They were away from mainstream platforms like Twitter and Facebook, and they were thoroughly infiltrated by pro-deplatforming activists and law enforcement informants. On the other hand, Telegram became an important arena in which attacks were planned, and where young people who were simply dabbling in jihadist content were pulled deeper into the movement. The results of deplatforming are now playing out in real time before our eyes, as ISIS supporters shop around for a new and stable home. As the dust settles, the positive and negative long-term consequences of major disruptions like the one initiated by Europol will become clear.

TamTam and Hoop, as the newest and most vibrant homes for ISIS, have themselves started decimating the network over the last week, but we are likely to see several months during which ISIS supporters attempt to establish themselves on new platforms. Just this morning, an ISIS supporter shared a tweet by researchers discussing the take down of content on Hoop and TamTam and wrote, “Stand your ground brothers, we’re getting to them, and there are blessings and victory in doing that.”

In other words, while we argue that we are disrupting them, they revel in the fact that they are keeping us guessing