Characteristics of Jihadist Terrorist Leaders: A Quantitative Approach

Characteristics of Jihadist Terrorist Leaders: A Quantitative

Approach

In June 2018 Mullah Fazlullah, the leader of the Taliban in Pakistan, was killed in a drone strike. This attack

can be seen as part of a decapitation strategy, which is frequently used by states. Often being perceived as a

symbol of their organisation, jihadist terrorist leaders take important positions in their groups and beyond. It

is therefore not surprising that counter-terrorism strategies often target the leadership of terrorist organisations.

However, open source data provide only limited information on these leaders and what sets them apart from other

members of their organisation. This Research Note brings together the fragmented information on 66 jihadist

terrorist leaders in a new dataset, suggesting the existence of a set of common characteristics of jihadist terrorist

leaders. Furthermore, when comparing leaders and followers, this study argues that, on the one hand they differ

from them when it comes to religious background and criminal records. On the other hand, they are quite similar

when it comes to characteristics such as education and socio-economic backgrounds. The most important finding,

however, is that leaders tend to have substantial battlefield experience. Many of them have fought in Afghanistan.

This suggests that Syria may become (or perhaps already has become) the breeding ground for a new generation

of jihadist terrorist leaders.

Introduction

In today’s culture, much of the general public seems to be fascinated by accounts on hunting terrorist leaders.

The wide variety of books and films on the search for, and elimination of, Osama bin Laden is illustrative of this

phenomenon. This case and other cases of targeted killings and organisational decapitation do, however, not

only capture the attention of the average citizen, it also illustrates the emphasis of this modus operandi within

counter-terrorism strategies [1]. Despite a substantial scholarly debate on the effectiveness of decapitation [2],

it is frequently assumed that the live or death of a terrorist leader has a significant effect on the longevity of a

terrorist organisation. This, then, leads to an assumption that there is plenty of knowledge on what sets these

leaders apart: what characterises them and to what extent do they differ from other terrorists? This assumption

is false, however.

Weinberg and Eubank have noted decades ago that information on terrorist leaders is “sparse” and “fragmented”.

[3] More recently, Hofmann has also held that basic knowledge on terrorist leaders is often still lacking. [4] Most

evidence on terrorist leadership characteristics still remains anecdotal. On the other hand, many studies have

been performed on the characteristics of (jihadist) terrorists in general. [5] However, even with the quantitative

analyses of, for example, Sageman and Bakker [6], no single common profile of a (jihadist) terrorist could be

established. Nevertheless, these studies have provided considerable insights in some of the basic characteristics

of (jihadist) terrorists.

It is the aim of this Research Note to follow in the footsteps of previous research on jihadist terrorists and to

improve our knowledge of the characteristics of jihadist terrorist leaders. Closing this knowledge gap will allow

a preliminary analysis of the similarities and differences between the characteristics of jihadist rank-and-file

terrorists and their leaders. Inspired by the work of Bakker [7] (and therefore indirectly by Sageman [8]), a

small database was built with data concerning the characteristics of 66 jihadist terrorist leaders active in the

ISSN 2334-3745 56 August 2018

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 12, Issue 4

years 2001-2017. Bringing together fragmented pieces of information can provide new insights, which might

lead to a partial rethinking of the wisdom of some counter-terrorism strategies.

Researching Terrorist Leaders

Following the call of Weinberg, Eubank and Hofmann to advance our basic understanding of (jihadist) terrorist

leaders, this Research Note firstly aims to gather open source data on the individuals in this population by

establishing an initial dataset on the characteristics of jihadist terrorist leaders. [9] This provides opportunities

to learn more about them and what sets them apart from jihadist terrorists in general.

In order to provide a first quantitative comparison between the two populations, many variables mirrored those

from the studies of Bakker and Sageman [10]. Some other variables have been added. The variables are ordered

in the three categories. The social background category is similar to Bakker’s, with regard to the variables. The

second category – career in jihadist terrorist organisations – is largely overlapping with his operationalisation

but includes some additional elements. While age and place of recruitment are variables Bakker also used,

the prior memberships in other jihadist terrorist organisations has been added here. This last variable may

help in understanding the career path of jihadist terrorist leaders. Lastly, this study looks into the battlefield

experiences of the leaders: did the leaders participate in wars and if so, where? This was not in the scope of

Bakker’s research, but may provide important insights in the development of jihadist terrorist careers.

For identifying leaders, the Consolidated United Nations Security Council Sanctions List has been used as a

starting point. [11] The heads of the jihadist terrorist organisations and their predecessors are included in the

sample. This has resulted in a dataset of 66 jihadist terrorist leaders who were active as leaders between 2001-

2017. These leaders are spread across 38 organisations with 18 of them still active as of October 2017, while

32 are dead [12] 7 others are incarcerated, 4 are inactive (e.g. in hiding without operational capabilities or

de-radicalised or disengaged). In one case no evidence could be found regarding his current status, while four

others are categorised as cases with contradictory information on their status. Here sources are not agreeing

as to whether a particular leader is active, arrested, deceased or inactive. The Appendix lists all individuals

included.

As mentioned earlier, the data were gathered from open sources. Data on the leaders were found in (auto-)

biographies, (inter-) governmental reports, newspapers, scholarly articles, think-tank reports, webpages such

as the ‘Mapping Militant Organizations’ section of Stanford University and the Counter Extremism Project, as

well as from speeches of, and interviews with, terrorist leaders. Furthermore, less than half a dozen of online

forums are used as sources (since they can provide translations of Arabic texts which are published by the

media outlets of jihadist terrorist organisations) [13]. While most of these sources can be considered to provide

reliable factual information, online forums and news articles are more problematical. Their partisan interest

may outpace their desire to provide correct information. As a result, during this study, multiple sources have

been used to crosscheck information.

The resulting dataset has been used in two ways. First, descriptive analyses have been used to draw a picture

of the characteristics of the jihadist terrorist leaders. Second, these results were used to form the basis for the

comparison with the characteristics of jihadist terrorists in general.

Characteristics of Jihadist Terrorist Leaders

The dataset resulting from the above-mentioned approach has provided the following insights on the social

background of jihadist terrorist leaders, their careers in terrorist organisations, and their battlefield experiences

Social Background

The first category of variables in this study concerns the social background of the leaders. This is detailed in

ISSN 2334-3745 57 August 2018

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 12, Issue 4

terms of geography, socio-economic background, education and faith, occupation, and criminal record.

Geography

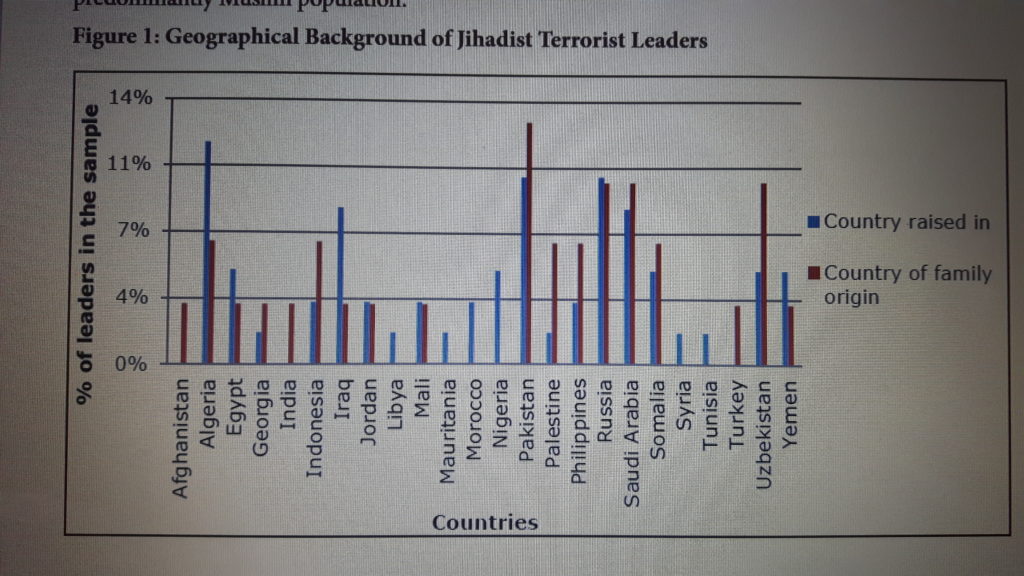

The leaders in the sample are from quite different countries of origin. While most leaders were raised in

Algeria (n=7), followed by Pakistan and Russia (n=6 each), no fewer than 21 different countries are identified

in this category. Furthermore, looking at the family origin of the leaders, 18 different countries are found, of

which Pakistan has the highest leader-count (n=4). As can be seen in Figure 1, most of the countries have a

predominantly Muslim population.

Figure 1: Geographical Background of Jihadist Terrorist Leaders

In addition, when comparing the countries in which leaders were raised and their current/last countries of

residence, it becomes clear that these are the same in 58,1% of the valid cases. 41,9% are currently living in

a different country than they were raised in or have died in a different country. This shows that while many

leaders emigrate at some point in their lives, most stayed in their country of origin.

Moreover, of those leaders who fought in wars or other violent conflicts (more information on this can be

found later in this section) and of which the country of where they were raised is known (n=34), 24 (36,4% of

total sample) fought abroad and 11 (16,7% of total sample) fought in their home country. Furthermore, of the

19 cases on which information on both the country where they had been raised and the country of military/

terrorist training has been found, 16 (84,2%) have had training abroad and 4 (21,1%) received training in their

home country. These findings demonstrate that leaders of jihadist terrorist organisations are often not limited

to their home country and tend to gain experiences abroad.

Socio-economic Background

Looking at the socio-economic background of the leaders, the data suggests that leaders are predominantly

from the middle classes of society (66,7%). The lower and upper class are equally represented in the sample

(16,7%). This finding contradicts some of the literature on terrorist leaders. According to both Leiken and

Sendagorta, leaders are recruited from the upper classes, while our data show that this not always the case. [14]

However, some caution in the generalising this statement is in order, since the number of cases on which data

on the socio-economic status was available is relatively low (n=18).

Education and Religion

It is often stated that many terrorists are relatively highly educated [15]. The new data on jihadist terrorist

leaders subscribes to this position (see Figure 2). 52% (n=13) attended university and of those, 12 graduated

and one did not. On the opposite side of the level of education scale, having received no formal education, is

0%

4%

7%

11%

14%

Afghanistan

Algeria

Egypt

Georgia

India

Indonesia

Iraq

Jordan

Libya

Mali

Mauritania

Morocco

Nigeria

Pakistan

Palestine

Philippines

Russia

Saudi Arabia

Somalia

Syria

Tunisia

Turkey

Uzbekistan

Yemen

% of leaders in the sample

Countries

Country raised in

Country of family

origin

ISSN 2334-3745 58 August 2018

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 12, Issue 4

Baitullah Mehsud. He is the founder of the umbrella organisation Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan. Moreover, six

leaders ended their education after secondary school. Interestingly, 25% (n=5) have ended their education

prematurely (i.e. without graduating). Moreover, 48% have graduated from university, while 25% did not

graduate from secondary school. Although a wide variety of levels of education could be found among the

leaders, most leaders are highly educated.

Further looking into the childhood years of the leaders, it becomes clear that most of them had a religious

upbringing, at least to some extent. Of the 20 valid cases, only three had no particular religious background.

Furthermore, there is one leader who converted from Christianity to Islam: Tarkan Tayumurazovich Batirashvili

(a.k.a. Omar Shishani). Moreover, of the leaders who received an Islamic upbringing, a wide variety of doctrines

can be seen (ranging from Deobandism to Salafism and from Wahhabism to Sufism). Interestingly, Sheikh Abu

Hashim Muhammad bin Abdul Rahman al Ibr (the arrested leader of Ansar al-Islam) changed from ShiaI to

Sunni Islam. This may also be considered as a case of conversion. Thus, while only represented to a minor

extent (n=5), converts who becoming jihadist terrorist leaders are a reality.

Figure 2: Levels of Education among Jihadist Terrorist Leaders

Occupation

With regard to the professional backgrounds of the jihadist terrorist leaders, it is hard to paint a general picture.

Of the 66 cases in total, 28 cases were available for analysis, since these are the cases data were found on the

occupational situation prior to or in between membership of jihadist terrorist organisations. The extracted

data were, on the one hand, very diverse; professions ranged from low to high on the societal ladder (i.e.

from employee of municipal maintenance services to medical surgeon). However, of all occupations found,

professions in which the leader takes a teaching role are more common than the other listed in our sample. In

eight cases (25,0%) jihadist terrorist leaders had held a teaching position. Furthermore, almost a third (32,1%)

have held no jobs. Although one explanation for this might be the young age at which these subjects joined

their first jihadist terrorist organisation (usually in their early twenties), no further statistical evidence has been

found for this in our sample.

Criminal Backgrounds

Concerning the criminal backgrounds of the jihadist terrorist leaders, the majority (22 of the 28 valid cases) had

been incarcerated in their past. The average time in prison (including those who had not been incarcerated) is

2.71 years, but most (n=9) have spent a total of one year behind bars. 8 leaders were incarcerated for 5 years or

longer. Overall, leaders tend to have been incarcerated for a period of time in their past. Of only 6 (9,1% of the

total sample) it could be determined that they had spent no time in prison. Figure 3 displays the incarceration

ISSN 2334-3745 59 August 2018

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 12, Issue 4

of the jihadist terrorist leaders.

Most leaders who have been found guilty in court (n=28) [16] have faced terrorist activity charges or were

accused of membership in a terrorist organisation (n=22). Furthermore, there are two counts of kidnapping,

four counts of illegal weapon possession, three charges of murder or murder threats, three cases of robbery and

petty theft. One future leader had been tried and found guilty of participating in a student protest, while there

was one account of undermining the ruling government by promoting the establishment of an Islamic state.

While the charges were very diverse, most leaders had been incarcerated or sentenced due to their terrorist

activities.

Figure 3: Incarceration Length of Jihadist Terrorists Leaders

Career in Jihadist Terrorist Organisations

The second category investigated was ‘career in jihadist terrorist organisations’. This category encompasses

the ages of joining the first jihadist terrorist organisation, recruitment (i.e. location of recruitment and

social affiliation), age of entering their current or previous organisation, and the number of jihadist terrorist

organisations the leader had been part of.

When joining their first jihadist terrorist organisation, leaders were, on average, 28 years of age. Moreover, 50%

of them entered the jihadist scene under the age of 26 and most of them were 21 or 22 years old. However, the

youngest age identified was 15 and the eldest was 61.

Related to the age of joining their first jihadist terrorist organisation is the recruitment context. Two variables

were examined: the location of recruitment and the effect of relatives, friends and other close acquaintances on

the joining of such organisations (i.e. social affiliation). Unfortunately, too little relevant data were found on the

latter. On the location of recruitment it can be said that Afghanistan often stood out. Of the 43 valid cases, 13

can be directly linked to Afghanistan in their recruitment. The Soviet invasion and occupation of Afghanistan

in the years since 1979, led many Muslims to Afghanistan to fight. This study does not equate joining the

resistance movement in Afghanistan with membership in a terrorist organisation, but the location has been

vital in the start of jihadist terrorist careers of these 13 leaders. Other places of recruitment have been as diverse

as the other countries listed above.

Comparing the ages at which the future leaders joined their first jihadist terrorist organisation with the age

at which they entered their current or last (in cases of being incarcerated or deceased) organisation, the ages

in the latter variable are generally higher, as one might expect. With the valid number of cases being 45, the

average age is 36. While most leaders were 29 or 33 when they entered their current organisation (n=5 for

ISSN 2334-3745 60 August 2018

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 12, Issue 4

both), 50% of all leaders were 33 or older. Abu Bakar Ba’asyir is an outlier with his age. Being the eldest case in

the sample with a birth date in 1938, he also exemplifies the phenomenon that leaders often tend to break away

from their first jihadist terrorist organization.

Of the 42 cases data could be found, 39 have been a member of at least one other jihadist terrorist organisation

than their current/last organisation. Nevertheless, the higher the number of other memberships, the less

common it becomes (see Table 1). Most leaders have been part of one other organisation (n=23, which is

34.8% of the total sample) while only one leader (Ahmed el Tilemsi) was part of four other jihadist terrorist

organisations (also the maximum number of other organisations in this sample).

Table 1: Interorganisational Mobility of Jihadist Terrorist Leaders

Memberships of other jihadist

terrorist organisations

Count Percentage of

total sample

Percentage of

total valid cases

0 3 4.5% 7.1%

1 23 34.8% 54.8%

2 13 19.7% 31.0%

3 2 3.0% 4.8%

4 1 1.5% 2.4%

Valid total 42 63.6% 100%

Total 66 100%

Battlefield Experience

The last category explored was battlefield experience. This section will look into the extent to which the

leaders had been actively participating in wars or other violent conflicts, and the locations of these battlefield

experiences.

Leaders who participated in wars or other violent conflicts are very well represented in the sample. Of the 38

valid cases, 35 score positively on this variable. It is not only a relatively high number within the valid cases,

also within the total sample it is a substantial amount. With 28 accounts of missing data, it can be stated that

at least 53% of the total sample has had frontline battle experiences – at least to some extent. While some have

participated in many conflicts, others have only had battlefield experience in one conflict. Nevertheless, 35

leaders have fought at the forefront on the battlefield. Jihadist leaders are predominantly veterans of war.

The locations of the wars and violent conflicts the leaders participated in are on the one hand diverse, but, on

the other hand, a pattern can be discerned. There are fourteen locations in which the leaders in our sample have

gained fighting experience. These stretch from Algeria to Indonesia but are predominantly Muslim countries.

Two main hot spots emerged. First, conflicts in the Caucasus have attracted and shaped 8 leaders. Second,

Afghanistan has had a strong appeal, 21 out of the 66 leaders in total (31,8%) have fought in the Afghan war

against the Soviet Union and/or later against the United States and its allies. A substantial number of the

leaders have had links to Afghanistan.

Comparing Leaders and Followers

In this section, a preliminary comparison will be made between (mostly) Bakker’s findings on the characteristics

of jihadist terrorists and our findings on jihadist leaders.

Geographical Background

With regard to jihadist terrorists in Europe, Bakker and Leiken argued that there are two types of terrorists

ISSN 2334-3745 61 August 2018

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 12, Issue 4

in terms of their geographical origins. [17] On the one hand, there are the first generation of immigrants

who were raised in a non-Western country and, on the other hand, there are the ‘insiders’ who were raised in

Europe but have a non-Western family origin. The connotation of insiders and outsiders is less applicable to

the jihadist terrorist leaders across the globe. While Bakker argues that most jihadist terrorists in Europe are

raised there and have different family backgrounds, the leaders in this dataset have predominantly been raised

in the country they are residing in.

Nevertheless, the locations of family background do seem to be related. As Jenkins also argued, family origins

of the jihadist terrorists in the United States often lay in North Africa, the Middle-East, South Asia and the

Balkan region. [18] Unsurprisingly, the jihadist terrorist leaders also come from these regions. The related

countries often display strict Islamic doctrines and it is therefore no wonder that these states are linked to

jihadist terrorist organisations with their extremist views regarding the teachings of Islam.

Socio-economic Background

Several scholars have found that the (jihadist) terrorist comes from the lower or middle classes of society. [19]

Nevertheless, Bakker has also found cases of jihadist terrorists in the upper classes in Western Europe. [20]

While Leiken argues that the leaders are recruited in the highest societal regions and the common members

of the terrorist group in the lower classes [21], this is not reflected in the analysis of our dataset. The present

comparison between followers and leaders leads us to conclude that there is no great difference between the

two groups when it comes to socio-economic status. We found that only a few leaders are from the lower or

upper classes of society. Just like among other members of jihadist terrorist organisations, the middle class is

very well represented. The differences are therefore not substantial.

Education

Nesser, Bakker, Hudson, and Jenkins have all argued that followers of terrorist organisations are often highly

educated. [22] Leiken, on the other hand, has argued that this is mostly true for the leaders. [23] The present

investigation has indeed found that leaders tend to be highly educated. Over 48% of them have received a

university-level education. However, in contrast to what Leiken argues, this, according to the other four authors

mentioned, is not only a characteristic of leaders. Furthermore, in both populations cases of ‘drop-outs’ (i.e.

those who did not finish the education they started) have been recorded. The leaders and followers therefore

do seem to have much in common when it comes to their level of education.

Occupation

(Jihadist) Terrorists often have a wide variety of occupations, according to Hudson and Bakker. [24] Although

unemployment has been found in their biographies, its rate is not significantly different from their peers in

society. Sendagorta also argues that unemployment in itself is not a very decisive factor in joining terrorist

groups. [25] Similar characteristics have been found in the sample of jihadist terrorist leaders. An interesting

outcome of our research is that there is a substantial portion of leaders who have had a teaching background

and/or were religious preachers. While Bakker and Hudson do not elaborate on the exact professions of the

members of jihadist terrorist organisations, it can be hypothesised here that this is a true characteristic of the

leaders, since they have been given a didactical role to play in the terrorist organisation.

Criminal Record

While Nesser argues that only a few terrorists have a criminal record, Bakker found that 25% of his sample

has been sentenced for criminal offenses. [26] Nevertheless, both authors agree that most of the terrorists do

not have a criminal record. However, the jihadist terrorist leaders show a relatively higher number of criminal

offenses. One-third of the sample has been incarcerated and 42% have been found guilty in court (some leaders

have been sentenced in absentia). While it is not always clear what the criminal charges of the members of

jihadist terrorist organisations generally were, it can be argued that the leaders of the current sample have a

criminal record more often than not. [27]

Religious Background

Some scholars have found that, in terms of religious backgrounds, jihadist terrorists have developed their faith

over time. Bakker, for example, found that only a small percentage had an Islamic upbringing (22%) and 58

ISSN 2334-3745 62 August 2018

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 12, Issue 4

of his 61 subjects had been identified as having increased their faith in the months prior to joining a terrorist

organisation. [28] Nesser has also found this, arguing that, before terrorists join an organisation, they have not

been very active in observing their religion. [29] Schuurman, Grol & Flower furthermore found that “converts

are considerably overrepresented” in Islamist extremism and terrorism. [30]

Leaders of jihadist terrorist organisations, however, do not match this description. Rather the opposite is true.

Only a small percentage did not receive an Islamic upbringing and the number of converts is quite low. This

contrast may be the result of the different focus areas of the above-mentioned studies. The secular and partially

Christian Europe in which the terrorist of the mentioned studies grew up in has provided a totally different

ideological context than the predominantly Islamic countries in which the leaders were raised. Nevertheless,

this difference in upbringing may be interesting to follow up in future research.

Circumstances of Joining the Jihad

Age

Bakker found that the ages of the subjects in his sample at the time of their arrest were spread large. With a

minimum of 16 and a maximum of 59, the average was 27 [31]. This relatively young age is also reflected in the

studies of Jenkins (average age of 32) [32] and Hudson (stating that on average the terrorists were in their early

twenties) [33] All three authors thus agree that terrorists are rather young.

The data from our exploration point in the same direction. However, as can be expected, the age of current

leaders is much higher. This higher age is consistent with the idea that leaders in general are more experienced

and thus older. The data thus show that although the distribution of ages varies greatly in both the jihadist

terrorist population and among jihadist terrorist leaders, the ages upon entering the jihadist scene are mostly

between 20 and 30. However, the leaders of jihadist terrorist organisations are substantially older than the

jihadist terrorists in the West.

Place of Recruitment

The places of recruitment can only be compared to a limited extent. Since Bakker’s sample only included

jihadist terrorists in Western Europe, his findings automatically differ greatly from the places of recruitment

found in our present sample. Nevertheless, both Bakker and Nesser argue that Pakistan is an important place

of recruitment. [34] This is also reflected in the sample of the leaders, but is not in terms of a breeding ground.

Only three leaders were reportedly recruited in Pakistan. It is Afghanistan that had the greatest recruitment

appeal for them. Still, no direct conclusions may be derived from this comparison, due to the different foci of

the studies.

In sum, the picture that arises is that leaders and their followers have both similar and differing characteristics.

The data of this research does not support a dichotomous conclusion. The leaders do not differ substantially

from the followers, but neither are they completely the same. Table 2 provides an overview of the discussed

characteristics and the way the characteristics of the leaders and followers are related.

Table 2: Summary of Comparisons between Leaders and Followers

Difference/similarity Legend

Geographical background + — Very different

Socioeconomic status + – Different

Education ++ + Similar

Occupation – ++ Very similar

Criminal record –

Religious background —

Age –

Place of recruitment –